However, the martyrdoms of the few were to prove less significant than the general threat of conscription. In March 1918 the massive German offensive on the western front panicked the British government into introducing a military service bill for Ireland. Never mind that the chief secretary for Ireland, Henry Duke, feared that `we might as well recruit Germans`. Lloyd George`s coalition rushed the bill through parliament, and Duke resigned. Such was the storm the measure provoked in Ireland that it was eventually withdrawn, but not before it had worked its unintentional effect of further radicalising the Irish population.

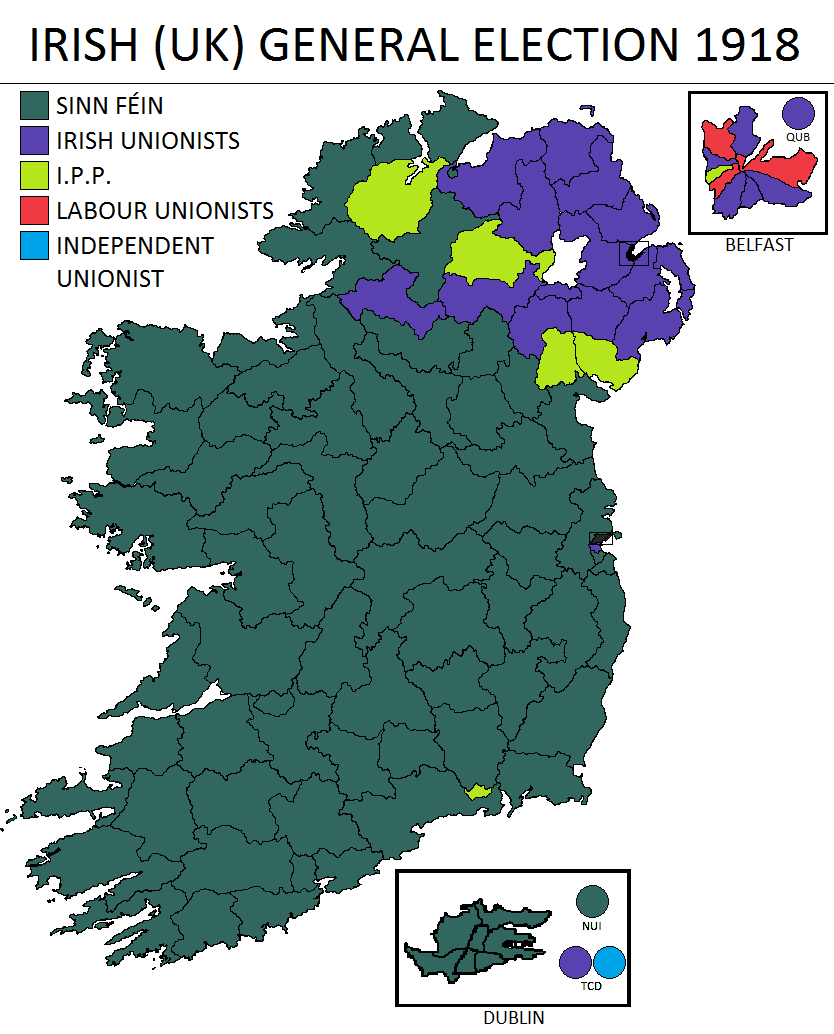

The cack-handedness of the British government fatally weakened a parliamentary Irish party committed to home rule for Ireland within the UK. The general election at the end of the war in 1918 saw Irish constituencies fall overwhelmingly to therepublican separatists of Sinn Fein.

Sinn Fein was an abstentionist party whose MPs were pledged to a boycott of Westminster. Instead the party`s MPs constituted themselves the Dail Eireann, the assembly of a self-proclaimed Irish republic. Ireland now witnessed a bloody and protracted tussle between two governments the UK and an Irish Republican `counter-state` each of which pretended to be the legitimate authority for the whole island, and attempted to govern as much of it as was practicable.

With no decisive outcome in sight, the British parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act in 1920, which extended home rule government under the crown to two separate entities: to the six counties of Northern Ireland, which were predominantly Protestant, and to the other 26 counties of southern Ireland. While the election to the new Northern Irish parliament was seriously contested, resulting in a Unionist majority, in the south no other parties dared to stand against Sinn Fein, except in the four university seats.

The impasse could only be resolved by negotiation. The result was a treaty concluded late in 1921 between the UK and the secessionist Irish Republic. In a sense the medium was the message, for the treaty was an implicit acceptance by the British of a sovereign Irish nation. Yet the terms of the treaty which granted effective independence to the Irish Free State, though a freedom tempered by an oath of allegianceto the crown proved divisive.

Ratification of the treaty narrowly squeaked through the Dail; but large parts of the Irish Republican Army wanted to fight on, either to secure better terms from the British or, less realistically, to realise the blue-sky dream of the Republic.

The result was a civil war in 1922-3 between the proand anti-treaty wings of Irish nationalism. Townshend draws particular attention to the role of the Neutral IRA, which claimed a membership of 20,000 men who had not been actively involved in the civil war.

Their appeals for peace were ignored, not least by the pro-treaty government: crushing internal resistance provided compelling proof of the new state`s effective sovereignty. Eventually, the civil war spluttered to a halt, without formal closure. As Townshend remarks, there were `no negotiations, no truce terms: the Republic simply melted back into the realms of the imagination` An appreciation of such ironies and unexpected disjunctions disturbs the smooth unreflective flow of traditional prejudice.

As Ireland, north and south, enters a decade of combustible centenaries, Townshend`s magnificent, unflinching history of the fight for independence holds out the prospect -however slim it might sometimes seem for truth and reconciliation.

By Colin Kidd -By arrangement with the Guardian

http://epaper.dawn.com/DetailImage.php?StoryImage=22_12_2013_013_003

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_War_of_Independence

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

آپ اور پاکستان : http://pakistan-posts.blogspot.com/2013/11/pakistan-basic-issues-need-immediate.html

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

آپ اور پاکستان : http://pakistan-posts.blogspot.com/2013/11/pakistan-basic-issues-need-immediate.html

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~