Inside Isis Inc: The journey of a barrel of oil

Isis controls most of Syria’s oil fields and crude is the militant group's biggest single source of revenue. Here we follow the progress of a barrel of oil from extraction to end user to see how the Isis production system works, who is making money from it, and why it is proving so challenging to disrupt, even with airstrikes.

By Erika Solomon, Robin Kwong and Steven Bernard

Source: http://ig.ft.com/sites/2015/isis-oil/

Where the oil is extracted

Isis controls most of Syria’s oil fields and crude is the militant group's biggest single source of revenue. Here we follow the progress of a barrel of oil from extraction to end user to see how the Isis production system works, who is making money from it, and why it is proving so challenging to disrupt, even with airstrikes.

By Erika Solomon, Robin Kwong and Steven Bernard

Source: http://ig.ft.com/sites/2015/isis-oil/

Where the oil is extracted

It is difficult to determine a definitive oil production figure for Isis-controlled areas. But it is clear production levels have dropped in the Syrian fields since they were taken over by the militants. Most oil fields in the area are aging and the group does not have the technology or equipment needed to maintain them.

A new air campaign on Isis oil by the US-led coalition started at the end of October and is now more effectively disrupting Isis's crude extraction. Production fell by 30 pct this month at al-Omar and al-Tanak, Isis's two top producing fields and the most targeted by the recent offensive. Up to now, however, it is still likely the most lucrative revenue stream for Isis's central leadership.

The price of the oil depends on its quality. Some fields charge about $25 a barrel. Others, like al-Omar field, one of Syria’s largest, charge $45 a barrel. Overall, Isis is estimated to earn about $1.1m a day.

OilfieldEst. production (bpd)Price ($/barrel)

| Oilfield | Est. production (bpd) | Price ($/barrel) |

|---|---|---|

| al-Tanak | 11,000-12,000 | $40 |

| al-Omar | 6,000-9,000 | $45 |

| al-Jabseh | 2,500-3,000 | $30 |

| al-Tabqa | 1,500-1,800 | $20 |

| al-Kharata | 1,000 | $30 |

| al-Shoula | 650-800 | $30 |

| Deiro | 600-1,000 | $30 |

| al-Taim | 400-600 | $40 |

| al-Rashid | 200-300 | $25 |

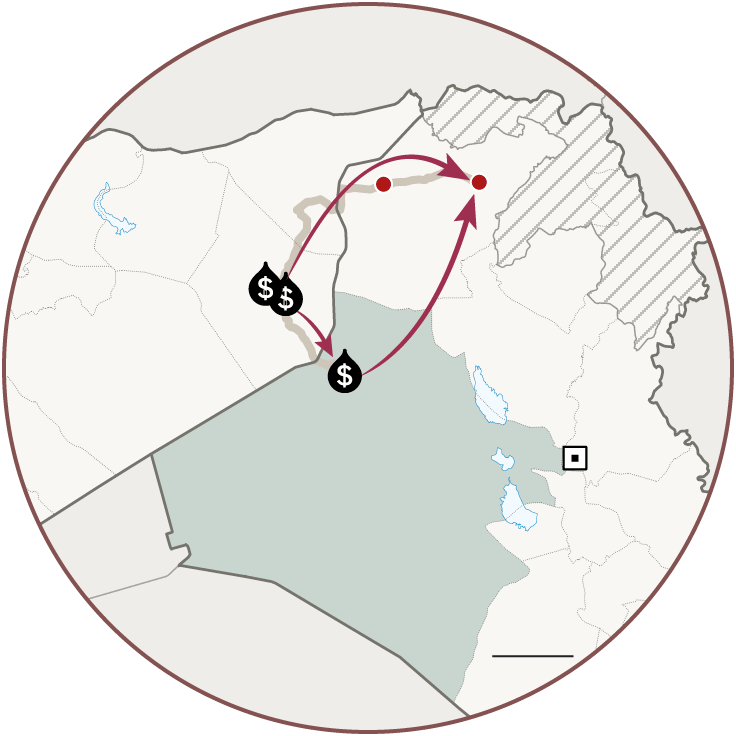

Selling crude oil

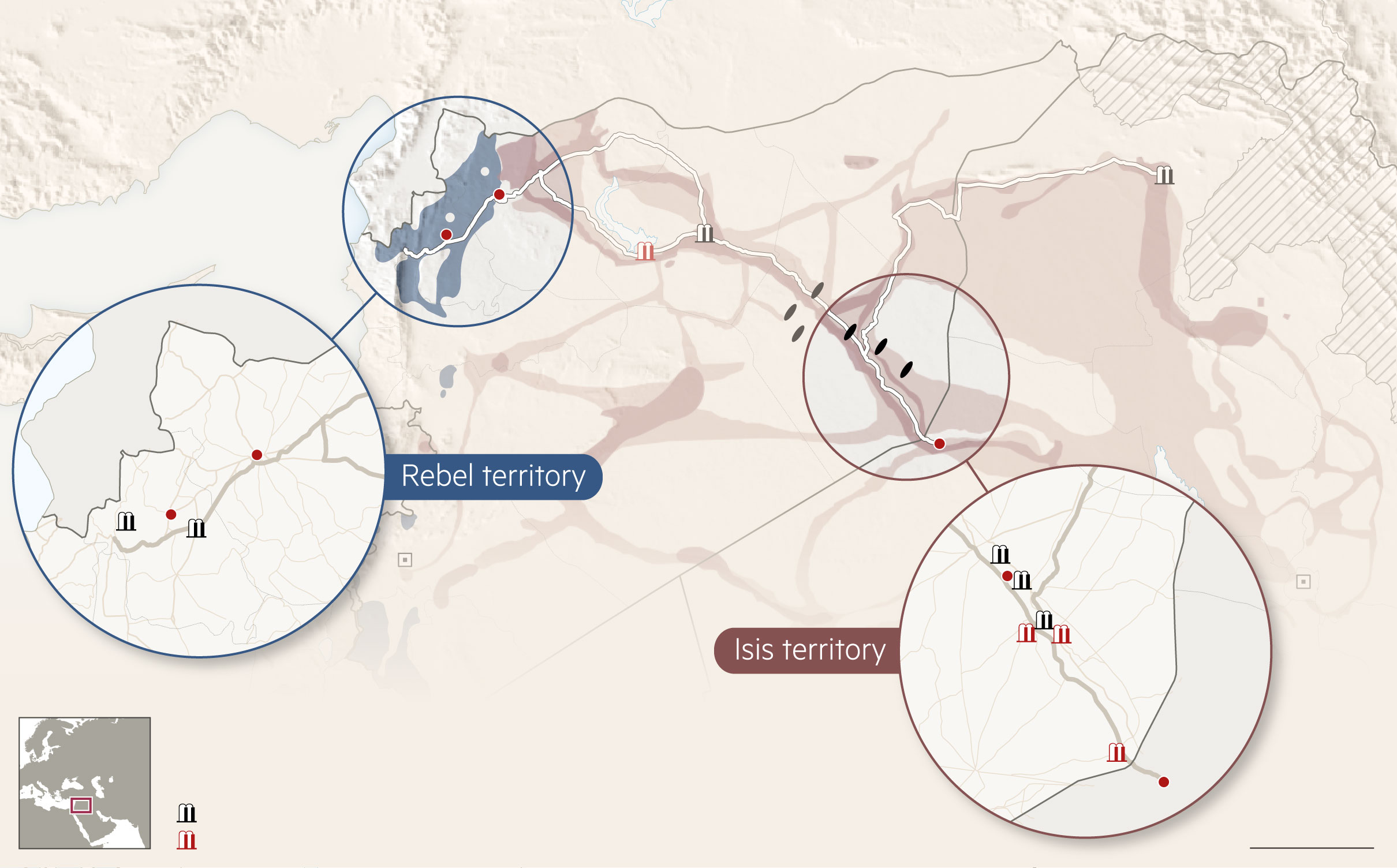

Though many believe that Isis relies on exports for its oil revenue, it profits from its captive markets closer to home in the rebel-held territories of northern Syria and in its self-proclaimed “caliphate”, which straddles the border between Syria and Iraq.

Though many believe that Isis relies on exports for its oil revenue, it profits from its captive markets closer to home in the rebel-held territories of northern Syria and in its self-proclaimed “caliphate”, which straddles the border between Syria and Iraq.

The group sells most of its crude directly to independent traders at the oil fields. In a highly organised system, Syrian and Iraqi buyers go directly to the oil fields with their trucks to buy crude. This used to result in them waiting for weeks in traffic jams that sprawled for miles outside of oilfields. But since airstrikes against oil vehicles intensified, Isis revamped its collection system. Now, when truckers register outside the field and pick up their number in line, they say they are told exactly what time they can return to fill up to avoid a pile-up of vehicles and make a more obvious target for strikes.

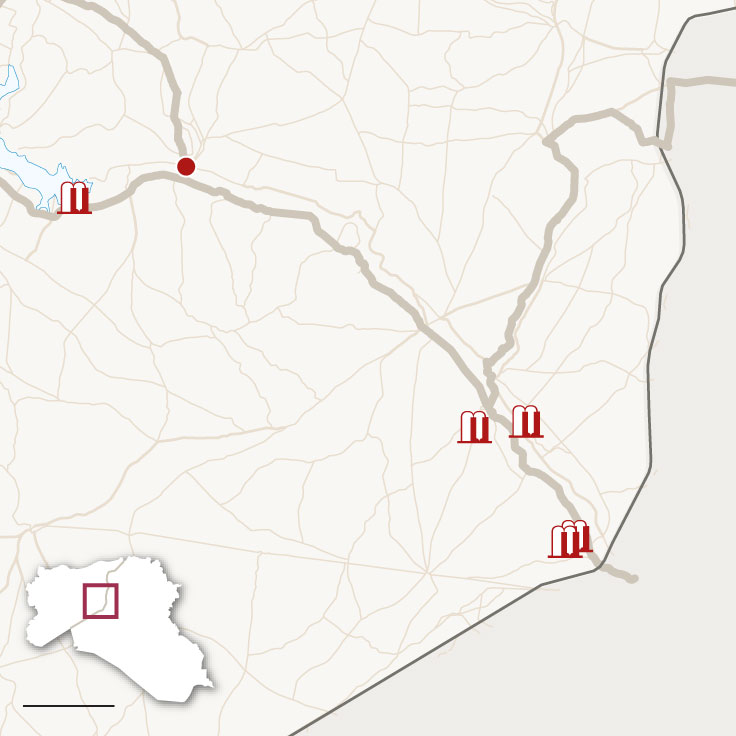

Oil refineries

Traders have several options after they pick up their cargo:

Traders have several options after they pick up their cargo:

Take the oil to nearby refineries, unload it and return to queue at the field—usually done by traders under contract to refineries.

Sell their oil on to traders with smaller vehicles, who then send it to rebel-held northern Syria, or east towards Iraq.

Try their luck selling to a refinery or sell it at a local oil market. The biggest are near al-Qaim on the Syrian-Iraqi border.

Most traders prefer to sell the oil on immediately and pick up a fresh number at the fields. They can expect to make a profit of at least SL3,000 (about $10) per barrel.

Sell their oil on to traders with smaller vehicles, who then send it to rebel-held northern Syria, or east towards Iraq.

Try their luck selling to a refinery or sell it at a local oil market. The biggest are near al-Qaim on the Syrian-Iraqi border.

Most traders prefer to sell the oil on immediately and pick up a fresh number at the fields. They can expect to make a profit of at least SL3,000 (about $10) per barrel.

Traders in Syria's eastern Deir Ezzor province say coalition airstrikes have not targeted their trucks by as much the coalition claims, and say Russia has targeted them more aggressively. Instead the attacks focused on disrupting the extraction process - hitting around the wells or facilities at the oil fields, as well as Isis vehicles. The goal does not appear to be to hit the actual wells but impede efforts to extract from them.

The bulk of oil refineries are in Isis-controlled Syria. The few in rebel-held territories have a reputation for lower quality output than the refineries in the east.

The refineries produce petrol and mazout, a heavy form of diesel used in generators – a necessity as many areas have little or no electricity. Because the quality of the petrol can be inconsistent and is more expensive, mazout is in greater demand.

Refining is done by local residents who constructed their rudimentary refineries after Isis's prefabricated "mobile" facilities were destroyed by coalition airstrikes. The owners make purchase agreements with the militants for their products.

There are also signs that in recent months Isis may have returned to refining. In interviews with traders, the FT discovered the group had bought five refineries since mid-2015.

At Isis refineries, the former owner stays on as a "front" man. The group supplies the oil; in return it takes all mazout production and splits the profits on petrol production with the original owner.

Traders say Isis has its own tankers that supply crude to its refineries from oil fields regularly. The group also appears to retain many of its earlier contracts with unaffiliated gas stations and other refineries.

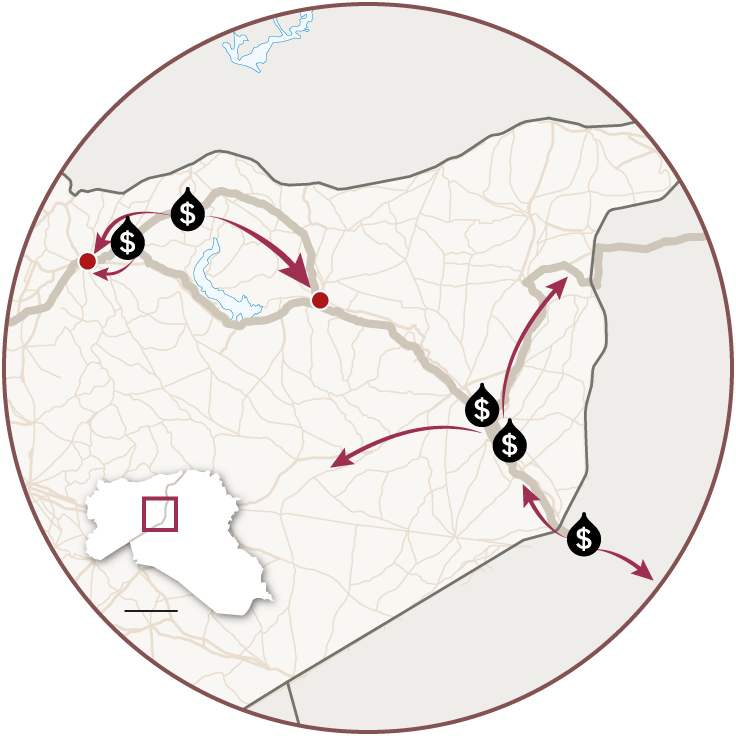

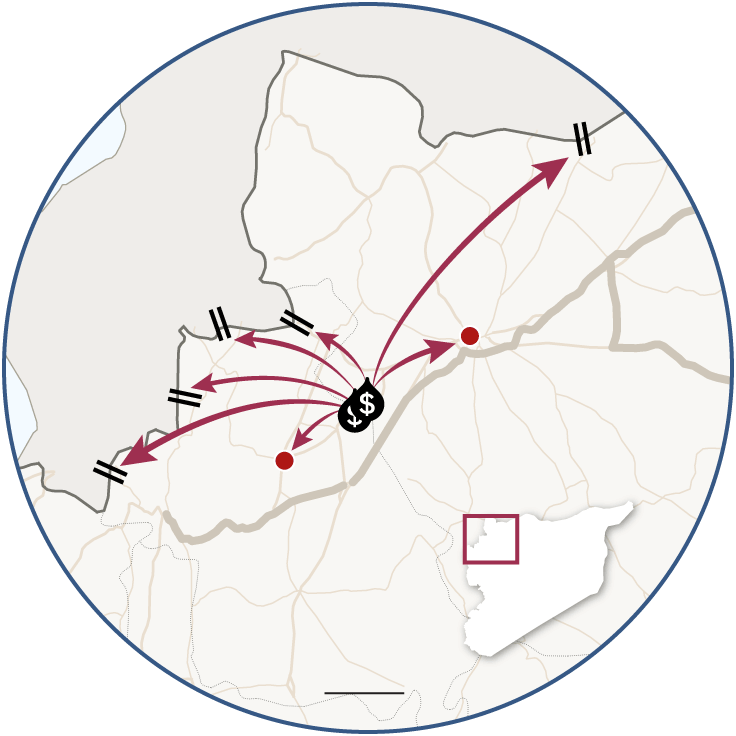

Fuel to market

Once the oil is refined, it is bought by traders or taken by dealers to markets across Syria and Iraq. At this point, Isis is almost completely disengaged from the trade. About half the oil goes to Iraq, while the other half is consumed in Syria, both in Isis territories and rebel-held areas in the north.

There are fuel markets throughout Isis-controlled areas and rebel-held Syria, often located close to refineries. Most towns have a small fuel market where locals buy and sell oil. But traders supplying these smaller markets often buy their oil in bulk from larger hubs.

Isis markets

There are larger Isis-controlled markets in towns like Manbij or al-Bab in Aleppo’s eastern countryside. Traders here must present a document proving they have paid zakat, a tithe, to buy oil without tax. Traders from rebel-held Syria who have not paid the tithe, must pay a tax of SL200 per barrel, or about $0.67.

Some privately-owned markets also levy taxes. Al-Qaim market, one of the largest in the region, charges buyers and sellers about SL100 ($0.30) per barrel of crude purchased.

In Isis-controlled Iraqi cities like Mosul, the fuel is sold at mini “petrol stations” with two pumps. They are ubiquitous on Mosul street corners and locals usually name the oil according to the part of Syria it came from. This helps buyers determine the quality of the oil and compare prices.

Two types of fuel are sold in rebel-held Syria: pricier fuel refined in Isis areas, and cheaper locally refined fuel. Residents typically buy a mix of both, and use the cheaper variety for generators and keep better quality variety for their vehicles.

Since the airstrikes began, prices of mazout and diesel in rebel-held areas have doubled. Prices of food are higher as well because transport costs are rising.

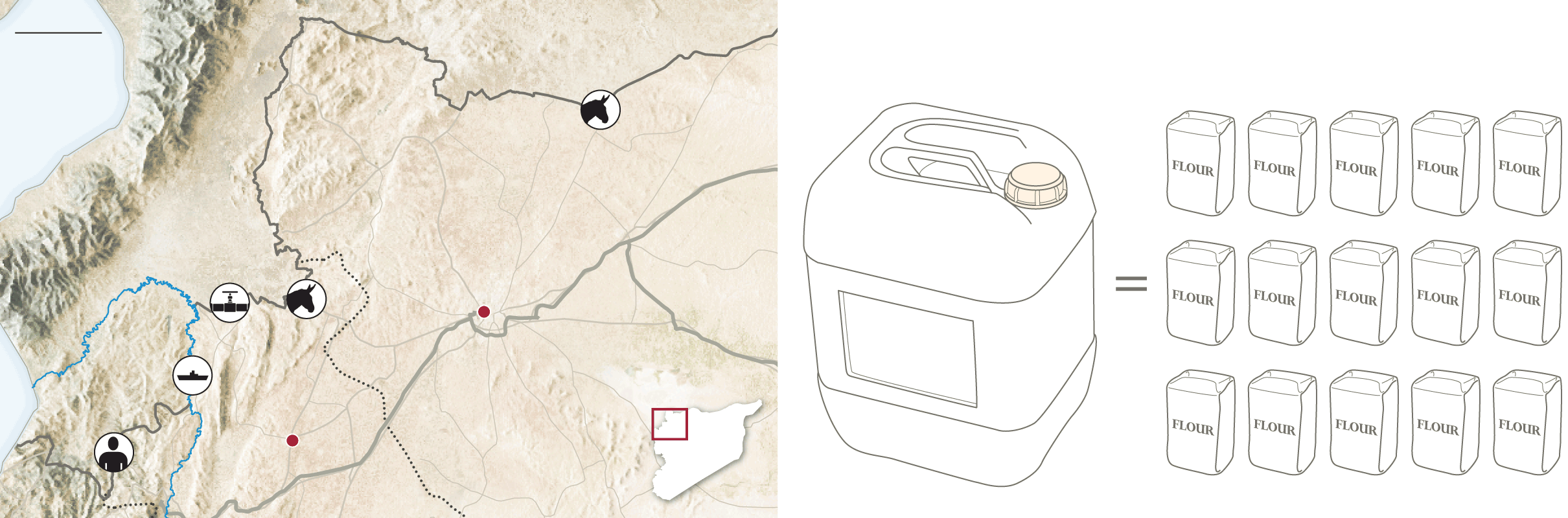

Fuel smuggling

With Isis only concerned with making its profits ‘at the pump’, smuggling fuel into neighbouring countries can be good business for entrepreneurial Syrians and Iraqis. Syrian smugglers say it has been declining in recent months, not because of tighter border controls but because the sharp fall in international oil prices make it unprofitable. But some determined smugglers continue their trade.

Most of the smuggling from the Syrian side has gone through opposition areas in the northwest. Locals buy fuel at the market, pour it into jerry cans and carry it over the border on foot or, in mountainous areas, by donkey or on horseback.

In Iraq, the bulk of smuggling through the northern Kurdistan region has been blocked, so locals say the route now goes south through Anbar province towards Jordan.

BoatWhen oil prices were high, smugglers loaded larger jerry cans (50-60 litres) of oil into metal tubs or small row boats and, using ropes attached to each river bank, pulled their cargo across the river and into Turkey. On the other bank, tractors picked up the supply and took it to a local informal market, where it was picked up by large trucks, which sold it on.

Pumps

PumpSome Syrian and Turkish border towns have co-operated by burying small rubber tubes under the border, such as at Besaslan. In recent months, Turkey has stepped up border patrols and are constantly digging out the makeshift pipelines.

PumpSome Syrian and Turkish border towns have co-operated by burying small rubber tubes under the border, such as at Besaslan. In recent months, Turkey has stepped up border patrols and are constantly digging out the makeshift pipelines.

On foot

FootA popular crossing point for smugglers carrying jerry cans of fuel on their backs has been from Kharbet al-Jawz in rebel-held Syria to Guvecci in Turkey. This has been largely shut down by Turkish forces, but the remote terrain makes it impossible to stop.

FootA popular crossing point for smugglers carrying jerry cans of fuel on their backs has been from Kharbet al-Jawz in rebel-held Syria to Guvecci in Turkey. This has been largely shut down by Turkish forces, but the remote terrain makes it impossible to stop.

Horseback

DonkeyIn places like al-Sarmada and al-Rai, smugglers have crossed the border by mule, donkey or horses that can carry four to eight jerry cans at a time.

DonkeyIn places like al-Sarmada and al-Rai, smugglers have crossed the border by mule, donkey or horses that can carry four to eight jerry cans at a time.

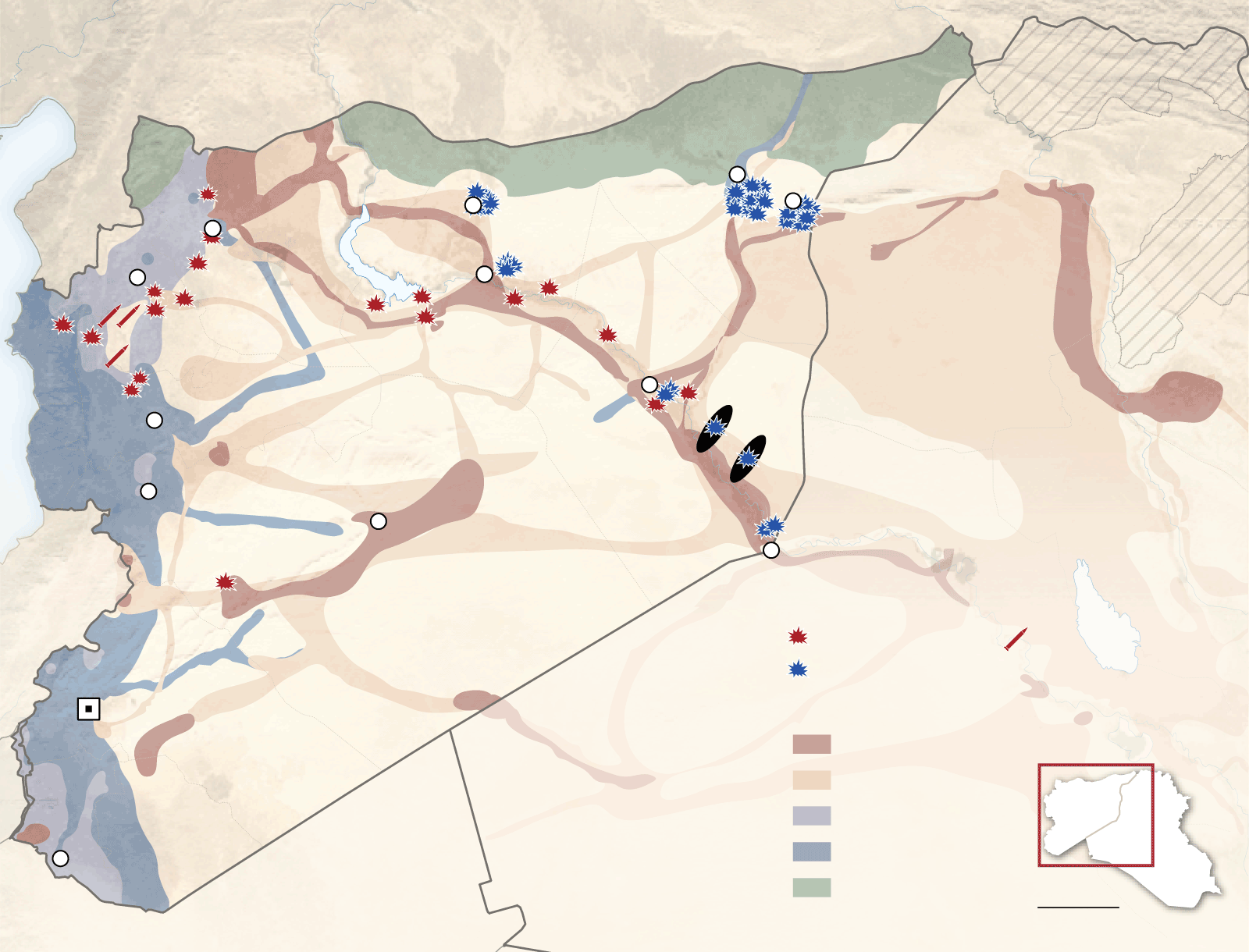

Airstrikes

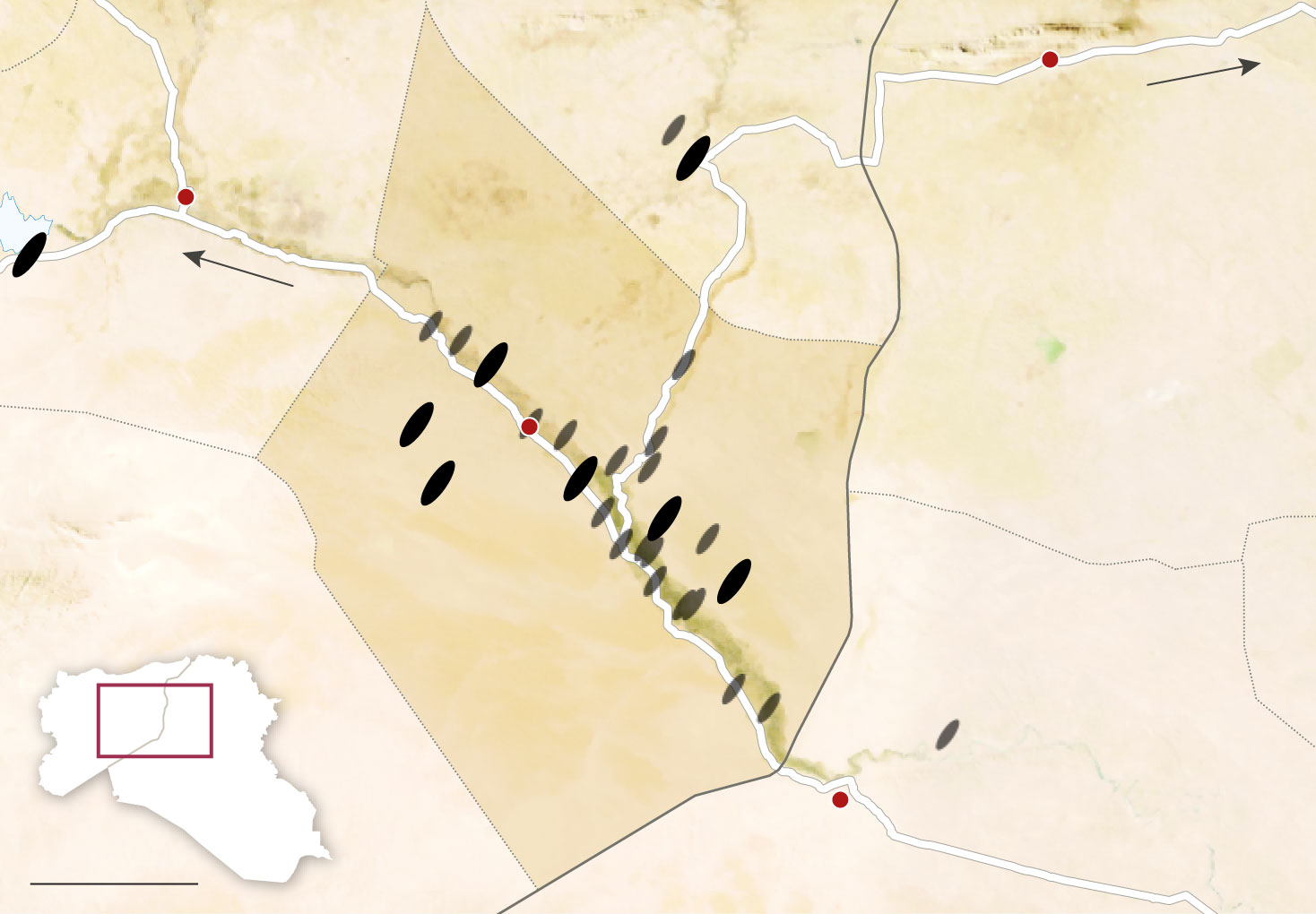

At the end of October, the US-led coalition launched a fresh assault on Isis oil infrastructure. These airstrikes were followed by Russian attacks, and intensified in mid-November.

At the end of October, the US-led coalition launched a fresh assault on Isis oil infrastructure. These airstrikes were followed by Russian attacks, and intensified in mid-November.

The coalition airstrikes against Isis oil operations have mainly targeted the oil extraction process, rather than refineries or oil markets. Bombs have hit Isis vehicles operating at the oil fields, and facilities for pumping or moving oil.

For example, the biggest single blow to Isis oil extraction, locals say, was a strike that took out the machinery that allowed oil workers to centrally control the wells at al-Omar field, Isis's single biggest oil source.

This had been critical because wells there can be 30km away from each other, and the machinery allowed workers to close down a well that was struck and avoid a fire spreading. Now, each well must be operated manually, which dramatically slows down the process of running the entire field.

Strikes on Syria from Nov 20

Sources: Institute for the Study of War, US Central Command,

US Department of Defense, FT research

These efforts to stop Isis earning money from oil is starting to have an effect. Production fell by 30 per cent in December at al-Omar and al-Tanak.

But it comes at a human cost. Civilian traders have been hit by an increasing number of strikes. Local civilians are angry about the new campaign and they fear for their own economic survival, which is now entangled with that of Isis's finances.

"This is considered our infrastructure, and destroying it like this...shows that the objective is to kill the Syrian people," says Omar al-Shimali, who lives in the rebel-held Aleppo province to the northwest.

Where Isis buys its bullets

Fighting can consume tens of thousands of bullets in a single day. Securing this ammunition requires a complex logistical operation